Tariffied

Feels like Déjà vu as tariffs and trade wars are back to filling economic news headlines. This week the Trump administration has threatened to impose tariffs on Canada and Mexico in addition to previously announced trade restrictions on China. A tariff is a tax imposed on goods imported into a country. Typically, they are levied in an effort to balance the price between imported and domestic goods thus incentivizing consumers to buy domestic goods. But tariffs serve various other uses; They can raise tax revenue, be used as a negotiating tool, protect intellectual property, and help balance trade deficits.

Protectionism, particularly tariffs, have a poor publicist in the economics world. At best they are often maligned as inefficient due to ‘deadweight losses’ - and at worse are framed as destructive. The Smoot Hawley Tariffs have become a common scapegoat for worsening the Great Depression and are frequently used as a bulwark against using tariffs today. Both of those points I would argue but nevertheless protectionism is largely repudiated, and “free trade” has become the norm. It’s my opinion that a lot of economic theory regarding international trade is impractical. Free trade orthodoxy promotes that specialization and comparative advantage are the path to growth. Supposedly, a nation should concentrate its factors of production on the industries in which it has a comparative advantage, and import everything else. But real-world economic history shows that development does not result from increasingly specializing at what one already produces well, but from learning to produce entirely new things. Certain industries foster this path of innovation better than others.

High-end manufacturing is a quintessential example of a “good” path industry. High-end manufacturing can absorb an immense amount of capital that can be invested in machinery, human capital, research & development, etc. - all of which foster innovation and create increasing returns. Additionally, the products of this investment are exportable and capable of infinite improvement themselves - such as semiconductors, airplanes, or quantum computing. And the institutional capital and processes behind developing these products tends to lead to the development of new innovations, thus creating a virtuous cycle. Economist Ian Fletcher coined this dynamic the “ladder of externalities”. Moreover, even if only a small portion of a nation is employed in manufacturing, its benefits flow through to the rest of a healthy economy and labor market. National security also must be considered for certain industries particularly when trade is done with an adversarial nation. None of this can be properly accounted for in traditional economic trade models.

Real world history also shows that protectionism has been positive for almost every major economic power's industrialization and tax revenue. Britian’s protection of the wool industry and the Navigations Acts, which restricted British trade to British ships was foundational in the growth and maintenance of the British empire. In the 19th century the confederation of German states established a customs union that lowered tariffs between them and imposed high tariffs on outside imports. The US implemented infant industry protection to grow its production of steel, textiles, and railroads. The EU to this day implements tariffs on cars, airplanes, and agricultural products. Today's reversion towards protectionism when viewed through the wider lens of history could be seen as a return to the norm, rather than a departure.

That's my best attempt at editorializing trade economics in less than 500 words. I actually wrote my senior economics paper in college arguing that a technologically dominant country, such as the US, with both a strong consumer and production base should use strategic tariffs to protect high-value industries. So this debate is not new, and likely isn't going away.

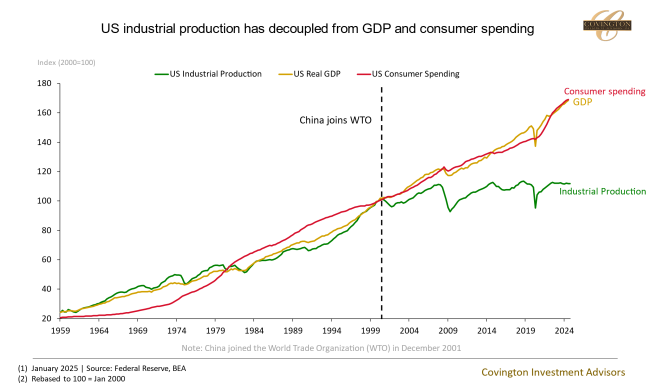

Which brings us back to what the Trump administration is trying to accomplish today by using tariffs, and how that will affect the economy and markets. The return to protectionism in the US could be seen as an effort to re-industrialize domestic production in certain sectors. Since China joined the World Trade Organization(WTO) in 2001, US industrial production has decoupled from consumer spending and GDP. Other data points with inflections around the same timeframe are rising manufacturing job losses, falling labor share of gross profits, and rising non-metro poverty rates. The monetary cost and benefits of the tariffs being proposed are likely exaggerated but will still have an effect. Taken at face value, Trump’s proposed goods tariffs (60% on China and 10% on all other countries) would increase annual customs revenue by about $450bn, but could also put upward pressure on prices. Luckily this time we have the benefit of hindsight from Trump's first term when trying to gauge what potential outcomes will be. During the 2016-2019 timeframe GDP growth was robust and inflation remained subdued which could be evidence that tariffs do not disrupt the economy significantly. One caveat to this is that the economy and inflation dynamics were structurally different in Trump's first term meaning their effects could also be disparate. I think ultimately increased tariffs will put slight upward pressure on inflation and rates, but effects will remain subdued if they are offset by cutting taxes and spending in other areas.

Bottom line. Tariffs and trade disputes will no doubt continue to fill headlines in economic news over the next four years and create volatility. It also can’t be said definitively that they will not be disruptive in some areas- after all they are somewhat meant to be. But I don’t think they will be so disruptive as to overpower the broader earnings cycle of the economy. And from a macro viewpoint, short-term pain can be beneficial to long term growth. The last six years is perhaps the best illustration that corporations are extremely resilient at adapting to tax/policy changes. This period has also shown that even if you know what events the future holds, their effects on corporate earnings and markets are difficult to predict. Sticking to sound investment principles while ignoring the noise will continue to be the best strategy going forward.

Commentary Disclosures: Covington Investment Advisors, Inc. prepared this material for informational purposes only and is not an offer or solicitation to buy or sell. The information provided is for general guidance and is not a personal recommendation for any particular investor or client and does not take into account the financial, investment or other objectives or needs of a particular investor or client. Clients and investors should consider other factors in making their investment decision while taking into account the current market environment.

Covington Investment Advisors, Inc. uses reasonable efforts to obtain information from sources which it believes to be reliable. Any comments and opinions made in this correspondence are subject to change without notice. Past performance is no indication of future results.